The #5 Spot: Rank Adams, Not Yang

For the New York left, the choice comes down to a simple question.

Indulging their masochistic tendencies - as they love to do - New York progressives have been ruminating on what would be worse: Mayor Eric Adams, or Mayor Andrew Yang. In the New York Times, Michelle Goldberg writes that although Adams seems more self-consciously reactionary, his base of Black support means he’ll necessarily be constrained from reverting to the worst excesses of the Bloomberg era. On his Substack, Ross Barkan concludes that this support will actually serve as the perfect cover for a conservative agenda, and that the non-ideological Yang will offer more opportunities for progressive governance.

Though it pains me to break with my first subscriber, I have to go with Goldberg on this one. But not so much for the substance of either candidate’s platform; I think the policies both Yang and Adams would pursue are broadly similar. But only a Yang win would unequivocally signal the death of collective civic life in New York City after more than 30 years of bleeding out. An Adams win would be grim indeed, but offers the possibility that help will come before our politics is totally exsanguinated.

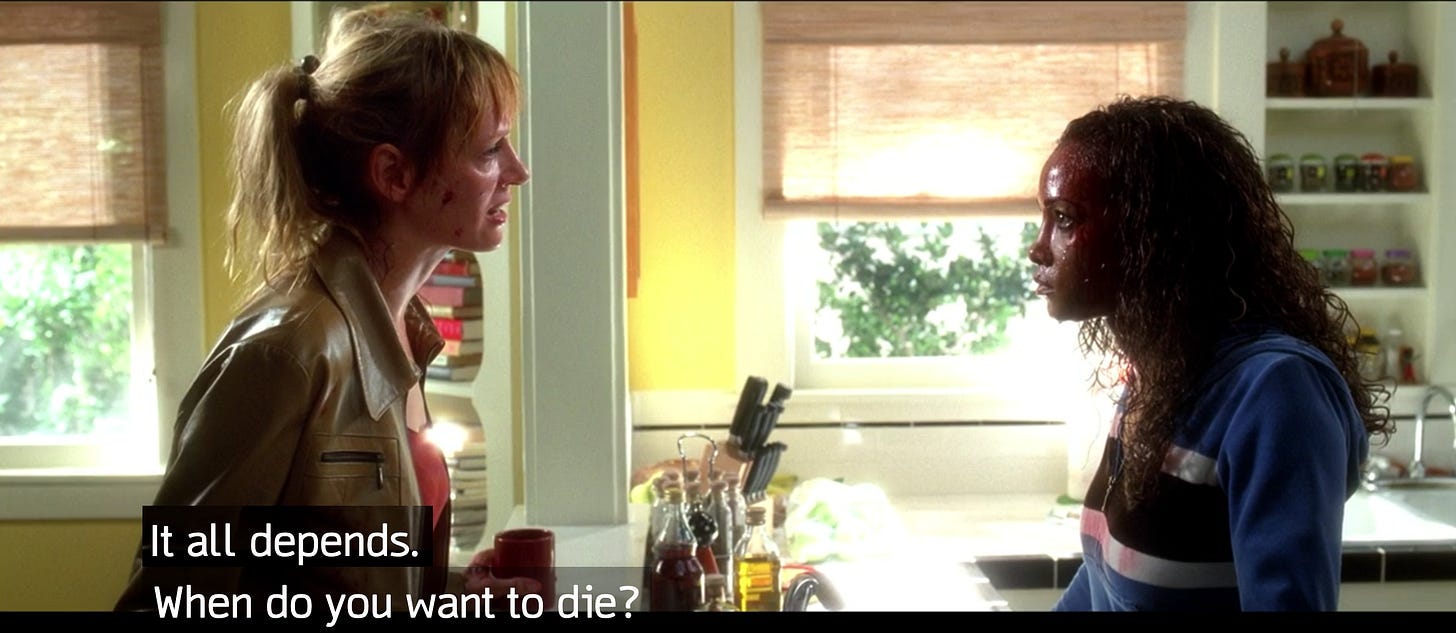

The real question for New York progressives is the one posed by the Bride to Vernita Green in the iconic opening sequence of Kill Bill, Volume 1: “When do you want to die? Tomorrow, or the day after tomorrow?”

In 1989, more than a million people voted in the Democratic primary for mayor of New York City - a turnout of 51 percent. Almost 400,000 more Democrats voted in their party’s mayoral primary that year as had voted in the previous one in 1985. It was almost as many people as had voted in the 1985 citywide general election. That mammoth turnout is what allowed David Dinkins to not only defeat the three-term incumbent Ed Koch by nearly 10 points, but win a clean majority in a four-way race after Koch captured 64 percent of the primary vote in 1985.

Reflecting on this achievement, The Chicago Tribune described a campaign operation that engineered unprecedented levels of voter mobilization:

“Dinkins had the support of nearly every major New York union in a city where organized labor still carries a considerable measure of political clout. The unions supplied Dinkins with 10,000 volunteers in the primary, as well as a political war chest and the ability to put together phone banks and registration drives.

Dinkins also drew on unprecedented wellsprings of support for a citywide black candidate. The now-familiar primary figures show that he won 29 percent of the white vote, 23 percent of the Jewish vote and 56 percent of the Hispanic vote.”

In November, Dinkins’ coalition of New York’s multiracial working class made him the first Black mayor in city history, defeating Rudy Giuliani by two and a half percent and keeping Gracie Mansion in Democratic hands for a fifth straight term.

It was the beginning of the end. Four years later, Giuliani edged out Dinkins in a rematch by just under three points, but that margin belied the coming 20 years of right-wing dominance in City Hall and the near total demobilization of New York’s liberal electorate and institutions.

By 1997, Giuliani had conquered city politics with sky-high approval ratings, buoyed by falling crime and a rising economy. The unions that just eight years earlier had backed the liberal revolt against Ed Koch now bent the knee to the new Republican regime. The Central Labor Council, a federation of 300 locals representing over a million workers, endorsed Giuliani’s re-election, as did DC37, representing over a hundred thousand government employees. SEIU 1199 stayed neutral, seen by many as a “de facto endorsement”. Giuliani still struggled with Black voters, but quadrupled his Black support from 1993. High-profile Black pastors and politicians endorsed him too.

Ruth Messinger, the Manhattan Borough President and Democratic nominee for mayor, never stood a chance. Writing in Time, Peter Beinart delivered this elegy for the last of the liberals as the country’s neoliberal turn finally arrived at its largest city:

“She has been deserted by the city's largest gay political organization, its biggest unions and all its major newspapers. Al Gore wouldn't campaign with her. She alienated Jews by embracing Al Sharpton, yet still lost the endorsement of two of New York's four black Congressmen...The 1997 race for mayor is to New York what the 1984 race for President was to the country. Messinger is Walter Mondale--a thoughtful, well-meaning politician with the great misfortune of being liberalism's standard bearer as liberalism collapses.”

Liberalism didn’t only collapse because it was overrun by the right; liberals themselves gave up on its defense. In 1989, more than a million people voted in the Democratic primary for mayor of New York City - a turnout of 51 percent. In 1997, just 411,00 showed up select a challenger to Giuliani - a turnout of 15 percent.

A reversal of fortune in every sense.

If liberalism collapsed in the 1990s, the new millennium set the wreckage on fire. Defying the odds, Republicans won a third straight mayoral election in New York City with Michael Bloomberg’s victory in 2001. The most improbable stars had aligned to make it possible, from September 11th to Bloomberg’s limitless fortune. But Democrats had a role to play as well. Though turnout in their primary had recovered somewhat, liberal voters were bitterly divided heading into November.

Allies of Mark Green, the incumbent Public Advocate, distributed fliers around white neighborhoods with a vulgar cartoon of his opponent, Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer, literally kissing the ass of the Reverend Al Shapton. Sharpton was a racially polarizing figure, with strong support among Black and brown New Yorkers but radioactive among most whites. Green denied involvement and wound up beating Ferrer by just under three points, but the incident had alienated vast swaths of the Democratic electorate. Bloomberg exploited this division, airing ads on Black radio stations linking Green to the fliers and enlisting Black surrogates to pitch a vote for Bloomberg as a protest against racist campaign tactics. Unconvinced by Green’s denials, the Bronx Machine refused to mobilize on his behalf.

In November, Bloomberg prevailed with a quarter of the Black vote - eclipsing the Republican record set in 1997 - and a majority of the Hispanic vote. Forty percent of Ferrer supporters in the primary reported switching to Bloomberg in the general.

As they had under Giuliani, organized labor made their peace with the neoliberal turn. In 2005, DC37 endorsed Bloomberg’s re-election before Democrats even held their primary for the first time in the union’s history. Other major unions soon affirmed their loyalty too. When Democrats did select their candidate - Fernando Ferrer, back for a second bite at the Big Apple - turnout in the primary plunged to just 480,000. Two months later, Bloomberg defeated Ferrer in the general by 20 points, the biggest margin of victory for a Republican mayor in city history.

But it wasn’t because Bloomberg had expanded his support; his raw vote total was almost identical to what he drew in 2001. Instead, Bloomberg had demoralized his opposition. Over 200,000 voters who cast a Democratic ballot in the last election chose to cast none at all this time around.

By 2009, liberal capitulation was complete. Bloomberg wanted a third term, so he bought off and bullied the City Council to change the law to allow it in just three weeks. Organized labor remained disciplined. Though DC37 endorsed Democratic nominee Bill Thompson following a contentious spat with the incumbent, major unions like UFT and SEIU 1199 dared not defy him. Democratic endorsers like Council Speaker Christine Quinn and even the newly elected Barack Obama were perceived to have abandoned Thompson, along with the city’s entire Democratic donor class. The month before the general election, New York Magazine reflected on how Bloomberg’s “imperial mayoralty” had totally subsumed political establishment:

“Forty-one years later, there is a one-man Establishment: Michael Bloomberg. Certainly there are other figures with real power. But in a way that wasn’t true two decades ago, their influence is circumscribed, confined to their narrow categories: real estate, culture, health care, banking. And, in terms of civic life, little of their power exists independent of their relationships with Bloomberg. The mogul-class push for the mayor’s term-limits extension felt like the last gasp of what’s left of the city’s old-line ruling class.”

But before liberal donors abandoned Thompson, their voters beat them to the punch. Just 310,000 Democrats cast a vote in their mayoral primary that year, a turnout of 11 percent - the lowest in modern city history. Thompson’s unexpectedly close margin in the general was a function of the fact that Bloomberg’s own supporters were growing as weary as the Democrats. Turnout collapsed in November to another record low, as hundreds of thousands more New Yorkers realized their input was no longer required.

The election of Bill de Blasio in 2013 is often interpreted as a repudiation of the runaway inequality and rampant police abuses that had come to define the Bloomberg era, and certainly that’s true. But it was also far from inevitable. The liberal coalition that emerged from twenty years of right-wing rule in City Hall was a shadow of its former self. Organized labor was split in the mayoral primary, but even as union momentum began to shift toward De Blasio, the New York Times noted the increasingly limited utility of their support:

“Even though candidates prize endorsements from labor unions, their value is hard to determine. In the past, many unions have sided with losing candidates, and in mayoral campaigns especially, union members may vote in accordance with their own political instincts, rather than hewing to the recommendations of their union.”

Partly, this is a function of a national decline in labor’s power that goes back decades. But it’s also a product of the distinct malaise in New York’s electorate. Though turnout in the 2013 mayoral primary ticked up to 690,000, that was still nearly 400,000 fewer voters than in 1989, despite the presence of over a million more registered Democrats on the city’s voter rolls. Vast swaths of New Yorkers have simply checked out of the political process. The one saving grace for the city was that by 2013, electing a Republican citywide had become virtually impossible.

Unless of course they’re running as a Democrat.

This brings us to the true significance of tomorrow’s mayoral primary. Though capital owns both parties in New York City - as it does everywhere else - right-wing elements have had to hustle in elections past if they wanted the most abusive oligarchs in power. They needed Republican voters too. Both Giuliani and Bloomberg built their support from a conservative base, then deployed various methods of attracting just enough Democratic defectors to win a general election. In our era of intense partisan polarization, such a strategy is no longer viable, and capital’s gambit to elect another right-wing mayor has moved to the Democratic primary.

Their candidate is Andrew Yang. Lacking any organic base in the electorate, he’s offered his campaign as the vehicle by which capital can return to City Hall in its most unvarnished form. Not a partnership, however unequal, with the political class - but direct rule by the city’s oligarchy, this time coordinated by Bradley Tusk instead of Michael Bloomberg. Their strategy is to piece together a base of the most reactionary constituencies in the Democratic electorate by pledging fealty to their parochial interests while absorbing atomized young voters who experience politics primarily through media consumption. Money and name recognition will take care of the rest.

If it works, it will be proof of concept that New York’s shattered left-of-center coalition can be reassembled at will by any agent of capital with sufficient resources and scarce principles. No labor support, no electoral history, no organic base required. It will prove that 30 years of political demobilization has reached its zenith, in which the remaining strength of the city’s liberal establishment is insufficient to prevent the hostile takeover of their own primary. That’s something even Michael Bloomberg with his infinite resources didn’t think he could accomplish twenty years ago. Tomorrow, we’ll find out if things have gotten so bad that a Reddit cringe poster can pull it off.

Adams is a conservative who will serve the interests of capital, but if he wins, that won’t be why. It’ll be because he has a genuine, durable base of support among real human beings in this city. If he wins, it will be proof of concept that politics is still possible in New York. The left will live to die another day.