Top New York Judge Madeline Singas Failed to Disclose Potential Conflicts of Interest

While Singas was Nassau District Attorney, her husband's company landed $1.6 million in contracts with the county - including his wife's office.

Madeline Singas is sworn in as Nassau County District Attorney in 2015 while her husband, Theo Apostolou (right) looks on.New York state law requires certain public employees and most elected officials to submit annual financial disclosure forms that document their assets, as well as any business dealings they or their relatives may have with government entities. This information is then made available to the public in order to discourage conflicts of interest and other forms of official corruption.

However, disclosure protocols are not uniform across all localities in New York. For example, the forms for statewide elected officials and members of the state legislature are all available online. But in Nassau County, interested parties must file a request with the local Board of Ethics under New York’s Freedom of Information Law in order to access the same documents. Until 2019, Nassau County required disclosure forms to be submitted on paper, and only maintained paper copies in its records. This meant that forms were often incomplete or improperly filled out, occasionally lost or missing altogether, and always onerous to locate, copy, and distribute in response to requests.

In April 2019, County Executive Laura Curran and then-District Attorney Madeline Singas announced that Nassau County would implement a new system of electronic filing so that local officials could submit their disclosure forms online. Though their stated purpose was cracking down on corruption, this new system wouldn’t do the one thing that would be most helpful toward that end: make the forms themselves available online for anyone to view. The local press expressed its skepticism at the time:

“The database will be made available to the Nassau County Board of Ethics and the county’s inspector general, but will not be made viewable to the public or any other county official. Joye Brown, a columnist with Newsday, asked: ‘What’s the difference between the Board of Ethics and the box in the basement if the public doesn’t have access to it?’

The county executive responded that the online financial disclosure platform was a step that was very important to the Board of Ethics. ‘They adopted this and they will have access to it,’ she said.

The county’s financial disclosure process was highlighted by Singas in a 2015 report that said the paper-based system did not ‘allow for the efficient, electronic cross-referencing between public officials’ disclosed relationships and potential county contractors.’”

Well, she was right about that. Case in point: in the six years that Singas served as Nassau DA, her husband’s company took in $1.6 million from contracts with the county, a fact which is conspicuously absent on her own financial disclosure forms. That includes contracts and purchase agreements made directly with the DA’s office, which Singas was responsible for approving. Considering that Singas was nominated and confirmed to the New York Court of Appeals - the highest court in the state - earlier this summer, this lapse in disclosure merits closer scrutiny.

Back in June, I filed a FOIL request for Singas’ financial disclosure forms for the years 2016-2021. Nassau County subsequently provided me with documentation for the years 2016, 2017, 2019, and 2020. Since disclosures are typically not filed until mid-year or later, the absence of this year’s form isn’t unusual. However, the lack of any documents for the year 2018 is conspicuous. If Singas never filed a disclosure for that year, it would be a clear breach of her ethical responsibilities as a state officer.

Nassau County’s financial disclosure forms consist of eight sections. For our purposes, the relevant ones are sections 3 (“Financial Interests”) and 7 (“Interests in Contracts”). In section 3, filers are required to list any employment they or their immediate family members have that generates more than $2,500 per year in income. In section 7, filers are required to list “any interest you, your spouse, or your dependent children have in any contract involving the County or any village, town, or municipality located within the County.” Each year, Singas noted that her husband, Theo Apostolou, is employed by the shipping and e-commerce firm Pitney Bowes, describing his position at the company as “sales,” and stated that section 7 was not applicable to her.

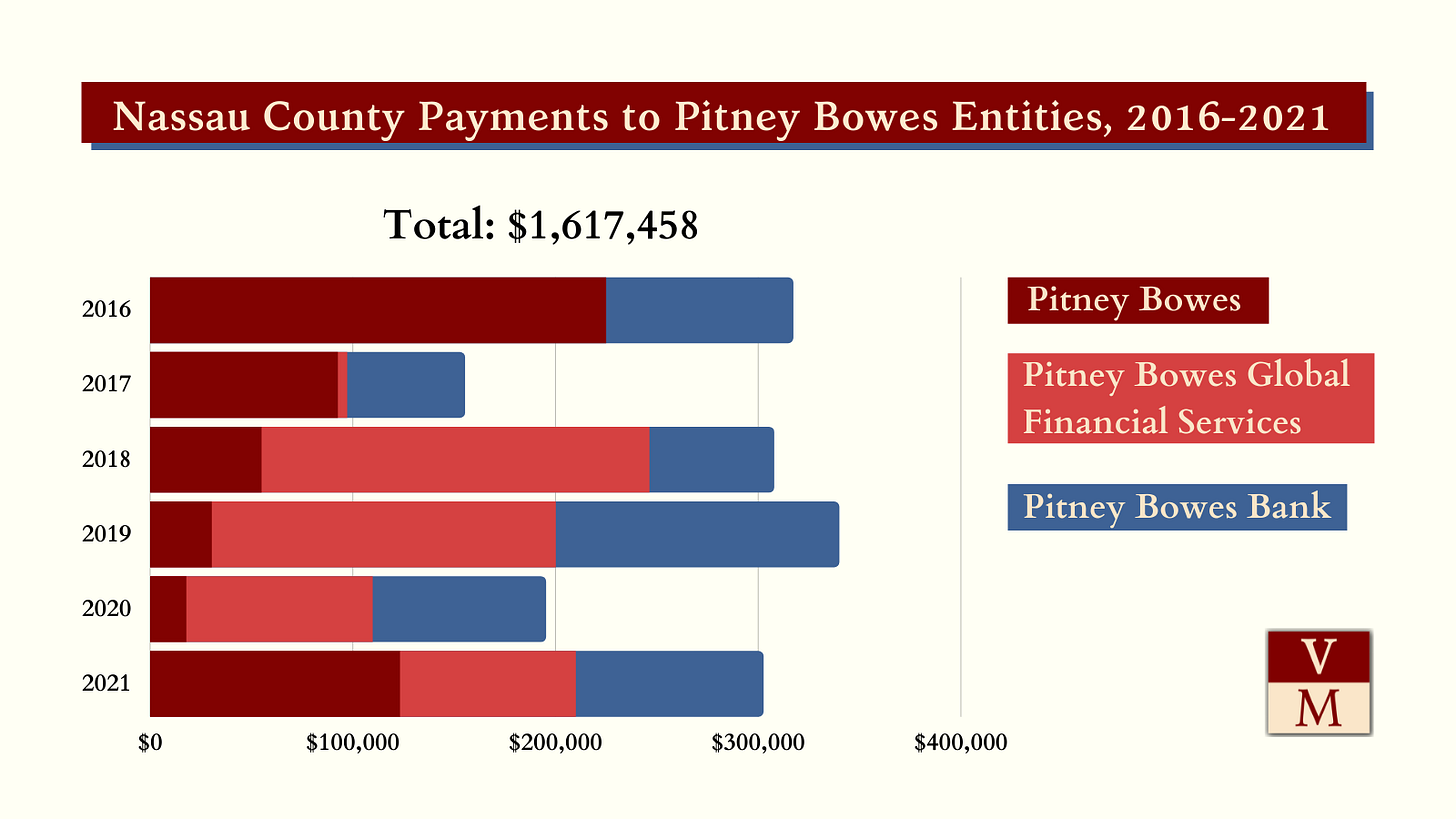

But in fact, Pitney Bowes is a vendor that serves dozens of local government entities. According to the Nassau County Open Checkbook database, the company and two subsidiaries - Pitney Bowes Global Financial Services and Pitney Bowes Bank - received over $1.6 million in payments from the county between 2016 and 2021.

Pitney Bowes is one of the few firms licensed by the United States Postal Service to manufacture postage meters, the kind you see in offices and mailrooms around the country. In fact, Pitney Bowes is the largest supplier of such devices nationwide. A big chunk of their business with Nassau County was leasing it meters and other mail equipment, providing maintenance and repair services on that equipment, and of course postage costs. As the use of paper mail has declined over the past 20 years, the firm has pivoted to other arenas in the shipping and e-commerce sector, as well as to certain software and technology ventures.

Separate from the question of whether Singas violated disclosure laws is the question of whether she had a prohibited interest in Nassau County’s dealings with Pitney Bowes. Not all conflicts of interest are prohibited, but even permissible ones must typically be reported - hence why her failure to do so is troubling in itself.

To assess these facts, I contacted Rebecca Roiphe, Trustee Professor of Law at New York Law School and an expert in legal ethics. Roiphe is a former prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, where she focused on white-collar crime. She currently serves as a member of the New York State Bar Association’s Committee on the Standards of Attorney Conduct, and as a liaison to the American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility.

In her opinion, the available evidence probably doesn’t suggest a prohibited interest in the Pitney Bowes’ contracts. According to guidance issued by the state comptroller’s office, a four-part formula is used to determine whether or not such an interest exists:

“First, there must be a ‘contract’ with the municipality. Second, the individual must have an ‘interest’ in the contract. Third, the individual, in his or her official capacity, must have one or more of the powers or duties that can give rise to a prohibited interest. Finally, the situation must not fit within any of the statutory exceptions.”

There’s no doubt that Pitney Bowes had contracts with Nassau County, nor that Singas had powers and duties that could give rise to a prohibited interest with respect to the firm’s contracts with her own office. From 2016-2021, Pitney Bowes made close to $50,000 from its business with the Nassau DA. As the chief executive of this agency, Singas would have been responsible for giving final approval on all of its expenditures.

For Roiphe, the real question is whether or not Singas had enough to gain from her office’s contracts with Pitney Bowes to constitute a genuine case of corruption. "What the law is trying to get at is whether or not someone is involved in, or is at risk of being involved in, some kind of grift,” she told me. “You wouldn’t want to hold someone liable on a mere technicality - if they don’t stand to gain much, or don’t have much of a role. If [Apostolou] is lower down in the company or doesn’t stand to benefit much, my sense is that this wouldn’t rise to the level of a prohibited interest.”

There’s also the possibility that one of the statutory exceptions could apply in this case, namely that the contracts are otherwise in the public interest. “If you just think about it on a practical level, you don’t want the government to have to go around making alternative deals that may themselves not be in the public interest just to avoid the appearance of a conflict that isn’t really serious,” Roiphe points out.

However, she sees potentially serious issues with regard to the disclosure law, which she says is much broader. “Disclosure is extremely important. A lot of government ethics depends on these laws, and they shouldn’t be minimized. You have to disclose a lot more than what would create a prohibited conflict of interest so that it can be scrutinized by the public.” So does that mean that Singas broke the law by failing to report that her husband’s employer is a county vendor?

“There’s a question of how much she knew when. You have to report something as soon as you become aware of it, but you can't be charged if you didn’t know what was going on. If she could really claim ignorance, she might not have violated the law,” Roiphe told me. The extent of Singas’ knowledge of Pitney Bowes’ business with Nassau County is a factual question that an investigative entity would need to examine if they felt it was warranted.

As far as this publication is concerned, it certainly is. Notice that the year in which the DA’s office transacted the most business with Pitney Bowes (2018) is the same year for which Singas failed to file a financial disclosure form. Notice also that the subsidiary in receipt of those payments, Pitney Bowes Global Financial Services, had never done business with the DA’s office prior to 2018. Whatever the nature of that contract, it wasn’t a holdover from before Singas’ time - it was a new one initiated after she took over as DA. Given that the appearance of impropriety is stark, someone should make an effort to inform the public as to whether or not any impropriety actually occurred.

Apart from the contracts with Pitney Bowes, Singas’ disclosure forms raise questions as to whether or not she was forthright about her family’s real estate holdings. Back in June, I reported that Singas and her husband owned at least three different properties in Queens County: Singas’ childhood home (a two-unit building in Astoria), 583 Seneca Avenue (a six-unit, rent-stabilized building in Ridgewood), and 214-10 23rd Avenue (a two-unit building in Flushing). Part of my motivation for filing the FOIL request was to see if I’d been able to identify all their properties using Google alone.

After their father died in 2012, Singas and her sister Effie inherited the family home. Sometime thereafter, it was clearly being rented out to other tenants, as indicated by several complaints filed by neighbors against the occupants with the Department of Buildings. In fact, a complaint from 2018 alleged that the building owners had illegally converted the basement into a third unit and were renting it out to a family. Inspectors visited the property multiple times, but were never able to obtain entry to investigate. In September 2019, Singas and her sister transferred the property to an LLC registered at the sister’s address on Long Island.

Curiously, the only year for which Singas disclosed receiving rental income from this property was 2019. In 2020, she listed her affiliation with the LLC that now owns the property, but didn’t report any rental income from it as she did the year before. Did Singas really not collect any portion of the income generated by her childhood home in the seven years between her father’s death and 2019? And if she didn’t plan to continue collecting this income in 2020, why would Singas affiliate herself with the new LLC?

Moreover, Singas never reported any rental income from 583 Seneca Avenue for any of the years on file, despite the fact that the LLC that owns the property is registered at her home in Manhasset. Singas likewise never reported any rental income from the property in Flushing, though what exactly is going on over there is less clear to me. Theo Apostolou, his brother-in-law, and a family friend named Vasiliki Orsaris all purchased this property together in 1998. Orsaris has been claiming New York’s STAR tax credit at the property since 2000, which is permissible only through one’s primary residence. But if she’s living in one of the units, who’s living in the other, and who are they paying rent to? If it’s Theo Apostolou, that would make three properties from which Singas failed to disclose rental income.

That’s also potentially problematic, according to Roiphe, depending on whether or not Singas deliberately hid this information. “If she’s not listing it and there’s a spot for including it on the form, that’s an issue. The question is would she just claim she wasn’t aware, and could you prove she was doing it willfully and knowingly. In terms of judicial ethics, I’d be very concerned if she’s intentionally hiding something.”

Once again, this would be a factual matter for investigators to address. Considering that Singas did report rental income from one of these properties in 2019, it’s reasonable to infer she knew that disclosing such income was required or expected. The public should be able to know the reason behind her failure to do so consistently.

I asked Roiphe how this set of facts compares with others she’s encountered in her career. She told me that when an investigator discovers that a public official failed to disclose a financial interest, it’s usually a red flag that may lead to further investigation and one of three possibilities: (1) A person is actively trying to conceal wrongdoing or a significant conflict of interest; (2) the person correctly determined that she was not required to make the disclosure; or 3) sloppiness. “Sloppiness itself is a concern,” she says. “As a citizen, that’s something I’d want to know about. It doesn’t necessarily mean she’s unqualified or shouldn't have the position, but it’s something that needs to be considered.”

Unfortunately, the public never had the opportunity to consider this information before Singas was confirmed to the Court of Appeals back in June; her nomination was rammed through the State Senate just two weeks after it was publicly announced. I submitted a FOIL application seeking Singas’ financial disclosures on June 10th, two days after her confirmation. It was marked as received on June 17th (the pony express of online applications, apparently), and I didn’t get the documents until July 20th. Even if someone had requested the forms the day her nomination was announced, they never would have been made public in time.

Ironically, it was Singas’ own half-hearted reforms Nassau County’s disclosure regime that ensured none of this information came to light before she secured one of the top judgeships in New York with next to no public scrutiny. Well, that and Mike Gianaris.

Mike Gianaris link in last paragraph gives 404