New York Democrats Preach “Pay Equity” While Their Own Employees Earn Poverty Wages

The State Assembly just passed a bill requiring government contractors to disclose their wage gaps. But the chamber's own finances reveal deep inequities.

Last week, the New York State Assembly voted to require government contractors to disclose their wage gaps in order to continue doing business with the state. Under the proposed legislation, contractors would have to file public reports detailing their “workforce pay averages, calculated by job category, gender, race, and ethnicity, and the difference between pay averages in each category.” Deborah Glick, a Democratic assemblywoman and the bill’s lead sponsor, says that the threat of bad publicity will incentivize employers to work harder at rooting out workplace discrimination.

As members debated the bill on Wednesday, Republican assemblyman Mike Lawler asked Glick if the state legislature includes similar demographic details in its own payroll data. He already knew the answer, of course. This was merely the wind up for a political jab: if his Democratic colleagues think that this sort of transparency will encourage “pay equity” in the private sector, why not mandate it for the public sector too? Anticipating his critique, Glick offered a preemptive - and perplexing - rebuttal:

“I don’t believe so. On the other hand, we are very public. So certainly everybody in my community knows who my staff are, and they can determine what category they fall into based on gender or race. So I think in that way it is obvious to our constituents.”

Does Glick mean to suggest that people can tell if she runs an equitable workplace by just sort of eyeballing her employees and trying to guess their race? This doesn’t seem like a very reliable method of assessment. Even if they guessed correctly, they’d still have to match the results of this racial appraisal to her office’s payroll data to detect any wage gaps, which seems needlessly onerous. Still, I figured why not give it a shot.

According to the assembly’s most recent expenditure report, Glick employs six full-time staffers and one part-time staffer. Of the six full-timers, five look mighty white to me. The other is a woman named Maryam Abdul-Aleem. I couldn’t find any pictures of her online, so I consulted an expert who said that the name “strikes me as Arab, but could also be Pakistani.” The part-timer’s name is Sarah Díaz, and I guess she looks Hispanic? Though I suppose this could be another Kathryn Garcia situation. One thing’s for sure: both of them make less than all but one of Glick’s white staffers. Pay equity for thee, but not for me.

Wage gaps within offices aren’t the only problem in the State Assembly. Disparities between offices are also common due to the chamber’s dysfunctional approach to human resources. Every year, the speaker allocates a certain amount of funding to each member so they can pay their staff, but not everyone receives the same amount. Speakers are always more generous with members of their own party, members with the greatest seniority, and close political allies. Deborah Glick is a Democrat who’s been in office since 1991, so her staff allotment is $356,000. That’s why she can afford to hire six people full time at competitive salaries.

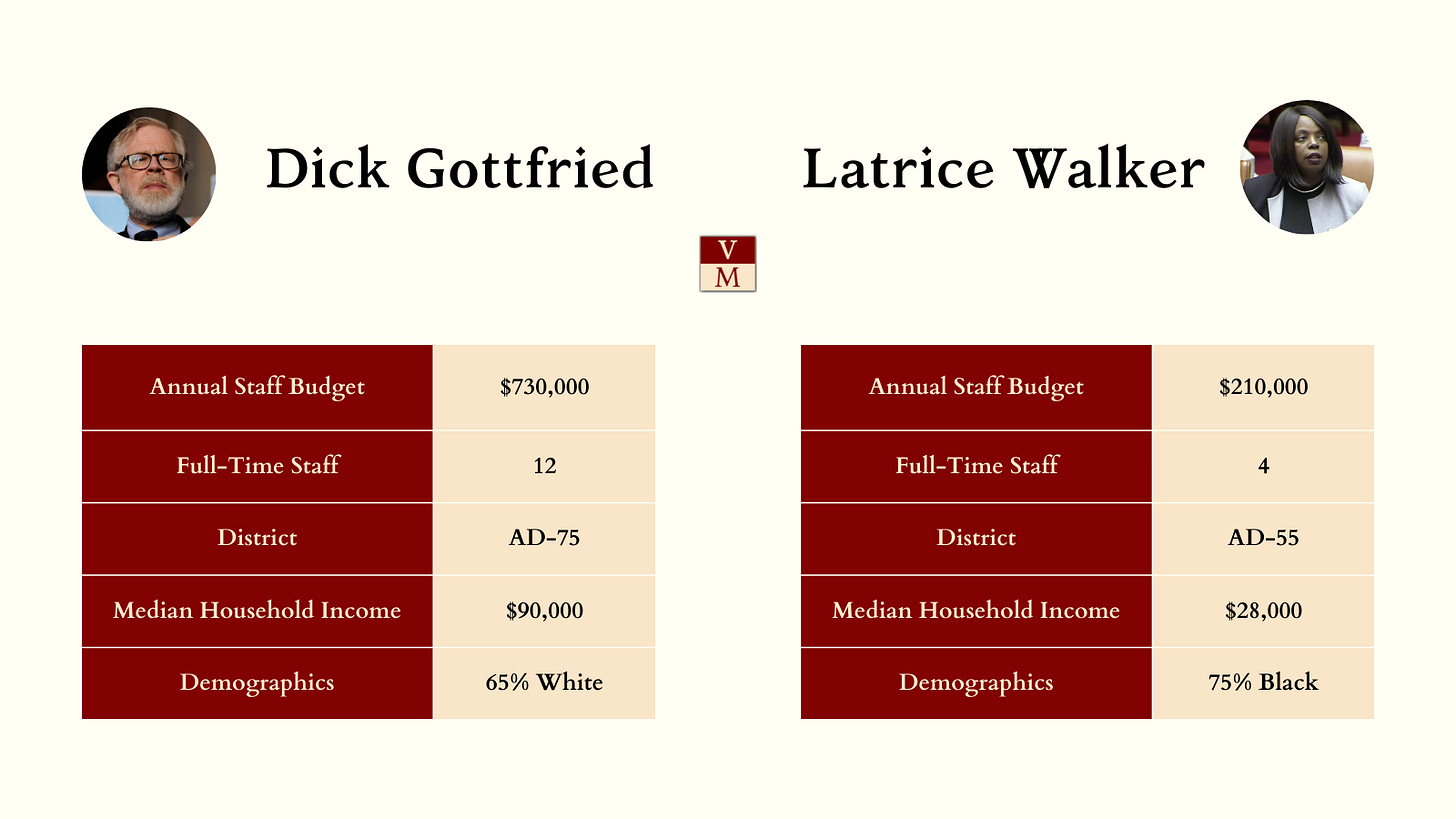

Now consider Latrice Walker, a Democratic assemblywoman first elected in 2014. Her allotment is $210,000, meaning that she can only afford to hire four people full time, and at lower rates than Glick offers. As a result, Walker has staffers doing the same type of work that Glick’s staffers do, but for less money. For example, both women employ a director of community relations and a constituent services manager, yet the wage gap between the two offices is substantial. There’s no reason to believe that Glick’s employees work any harder or have more experience than Walker’s to justify this kind of disparity.

In fact, it defies belief that these staffers could have more work to do in Glick’s office than in Walker’s. Glick’s district covers some of the poshest neighborhoods in downtown Manhattan - including the West Village, TriBeCa, and SoHo - and has a median household income of $105,000. Walker’s district mostly covers the Brownsville section of Brooklyn and has a median household income of $28,000. One of New York’s poorest, blackest neighborhoods has fewer people working for less money to meet greater need than some of the wealthiest, whitest enclaves in the city. That doesn’t strike me as very equitable.

Luckily for her constituents, Latrice Walker is a Democrat, and so her annual staff allotment will never fall below the $185,000 floor that Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie informally sets for his conference. Unfortunately for Mike Lawler’s constituents, he was the only GOP challenger to defeat a Democratic incumbent in 2020, and so his annual staff allotment is $115,000. On Friday, I spoke with Lawler about how difficult this makes it for him to provide adequate services to his Rockland County district.

“The allotment that we’re given for the number of residents in our district is peanuts - it’s less than one dollar per resident,” he told me. “We live in a high-tax, high-cost state, and you have to pay people well. I have one full-time chief of staff, and he works a lot of hours. Then we have a rotating, part-time schedule. And we do a lot. My office is extremely active, extremely responsive to our constituents. But we could do so much more if we had the resources to make everyone full time.”

Lawler says that he structures his payroll this way - as opposed to hiring two people full-time - because he needs staff who are properly equipped to interact with the diverse communities he represents. “My district is the most diverse one in the Republican conference. We have a large Orthodox Jewish community, one of largest Haitian communities in the state, a growing Hispanic population, a Southeast Asian community. We have a lot of different needs throughout the district and I need to have a staff that is reflective of that.”

Lawler raised this point with Glick during last week’s debate over her pay equity legislation, but she didn’t seem persuaded - or even interested in hearing him out. When he asked her how much she receives for her own staff allotment, she again offered a preemptive rebuttal before Lawler fully articulated his point:

Glick: “Well, I know that it is always your intention to frame a question in a way that posits your perception. I have no idea whether your constituent services spend as much time as mine do [at work], and I have no idea whether the level of committee work that your staff here might do is commensurate with the committee work that my staff does.”

Lawler: “My total staff allotment is $115,000. Would you say you get more than that?”

Glick: “Yes, I’ve been here a lot longer than you have. And I believe we did discuss the fact that some seniority might be a little bit different.”

It’s true that Lawler and Glick frame this issue differently. She believes that the size of a legislator’s staff and the salaries they enjoy should correspond to the legislator’s length of service in office. In this framing, staff are a talisman that symbolizes a politician’s personal achievements in government. Lawler believes that staff size and salaries should at least be sufficient to meet the needs of a legislator’s district and fairly compensate the people working to meet them. In this framing, staff are the means by which politicians fulfill their obligations to the public, as well as workers who have a right to decent treatment from their employer.

Between the two, only Lawler’s framing could be described as equitable. Glick’s framing is what leadership uses to justify even more preposterous disparities. Richard Gottfried, the assemblyman right next door to Glick in Manhattan, has been in office since 1970. His annual staff allotment is a jaw-dropping $730,000, enough for a retinue of 12 full-time employees. Apparently, New York’s lack of term limits means that the people of Chelsea and Murray Hill (median household income: $90,000) deserve three times as many people working for them as the people of Brownsville. Equity, indeed.

The State Assembly’s parsimonious method of allocating payroll funding incentivizes members to wring as much labor out of their staff as possible for as little money as they can get away with. As a result, the chamber is notorious for its low pay and exploitative working conditions. Hundreds of full-time employees earn well under $35,000/year, at jobs that demand well over 40 hours/week, in jurisdictions with some of the highest costs of living in the country. But don’t think it’s only Republicans who have an aptitude for management. Some of the assembly’s most liberal Democrats are also some of its most creative bookkeepers.

For example, Yuh-Line Niou of Lower Manhattan pays most of her full-time employees around $30,000/year. In the most recent 12 months on record, her legislative director earned just $29,803. She uses the savings from these poverty wages to maintain a large, rotating cast of precarious laborers under part-time and temporary designations - talk about a sweatshop queen! Before she left the assembly earlier this year to take up a post as Deputy Borough President in Brooklyn, Diana Richardson of Crown Heights had a full-time employee earning just $28,210/year. Catalina Cruz of Jackson Heights, Queens also pays her junior staffers around $30,000/year.

It’s important to note that someone making $15/hour at 40 hours/week and 50 weeks/year would earn $31,200 before taxes. The assembly doesn’t disclose contracts of employment, so it’s impossible to know for sure how many hours a given staffer is expected to work on paper. But the culture of Albany is one in which 40 hours/week is the minimum that most people are expected to work, regardless of what their contracts say. The result is that many employees of the legislature that set New York’s minimum wage at $15/hour in 2016 are working for less than that amount today.

The pay might be brutal, but at least these three are getting a big staff out of it. By contrast, hardly anyone seems to be working in Bobby Carroll’s office. The Park Slope assemblyman has two part-time legislative aides who both earn $35,000/year, while the majority of his allotment gets sucked up by his only full-time employee: a chief of staff who earns $110,000/year. The fact that both legislative aides are women and the chief of staff is a man creates a real whopper of a gender pay gap. On the other hand, both aides are white and the chief of staff is an Italian-American, so the racial pay gap is actually reversed. How they get any work done with only one full-time employee is a bit of a mystery, unless of course the “part-timers” aren't quite so part-time.

When I asked Lawler what he thinks about the assembly’s reputation for these types of accounting gimmicks, he didn’t mince words. “In many respects, given the amount of work, and the seriousness and time sensitive nature of governmental work, it borders on abusive to require these folks to work so many hours and be paid so poorly. It really is a question of fairness, and how we can best serve the taxpayers and the constituents that we all represent.” Still, it’s important to note that not all members with stingy staff allotments behave this way.

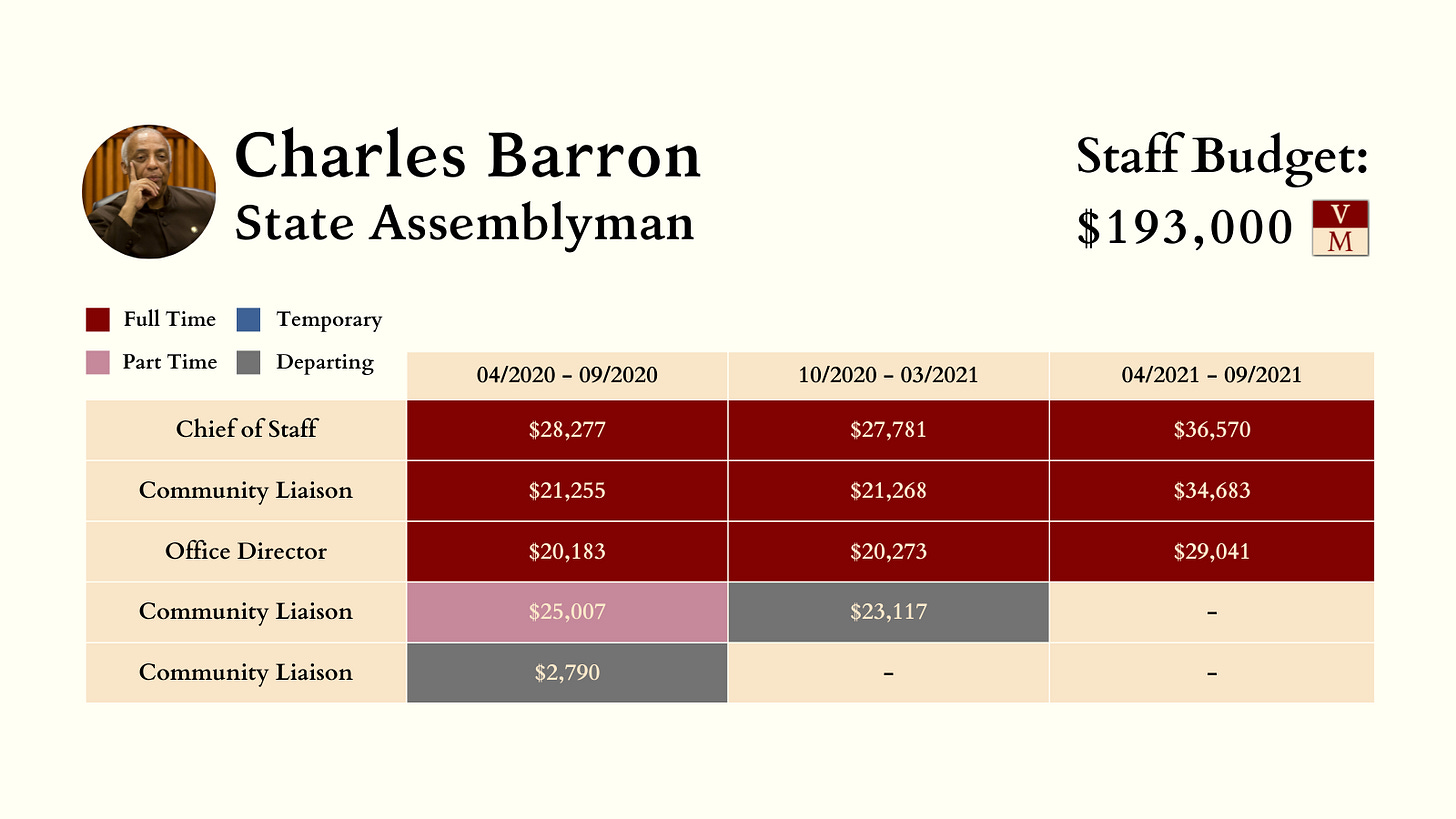

For example, Charles Barron has represented the East New York section of Brooklyn in various capacities for 20 years. During his time in the assembly, he hired only as many people as his allotment could cover at a living wage. Of course, the former Black Panther and reigning King of Takes is an unusually caring boss. During his first stint on the City Council, Barron got between his chief of staff Viola Plummer and the three cops trying to arrest her at the behest of council speaker and mayoral hopeful Christine Quinn right in City Hall. Barron was rolling up his sleeves and getting ready to rumble before Plummer agreed to leave. As they departed, Barron called out: “Christine, you’ll never be mayor!” And guess what - she never was! Later, he told the media that he was considering placing Quinn under a citizen’s arrest.

Ultimately, Lawler voted in favor of Glick’s bill requiring state contractors to disclose their wage gaps. He just wants the same standard to apply to the government too. “We always want to legislate and dictate to the private sector, but the legislature is notorious for exempting itself from the very thing they require of others. They repealed 50-A last year” - the state law that shielded the disciplinary records of police officers from public scrutiny - “but one of the first things the legislature does every session is pass a rule exempting itself from the Freedom of Information Law.”

To that end, Lawler rolled out legislation earlier this month to set a uniform staff allotment of $250,000 annually for every member of the assembly. No more young legislators struggling to provide services in Brooklyn’s poorest districts, no more 50-year veterans commanding armies of staffers in Manhattan’s toniest neighborhoods, and no more upstate Republicans turning over the couch cushions trying to meet payroll. “All of us represent roughly the same number of people, our constituents have the same needs, and our staff should be paid commensurate with the work they’re doing. Therefore, we should be given the same allotment,” Lawler concludes.

That sure sounds like equity to me, but maybe it sounds a little too equitable to assembly Democrats. So far, only fellow Republicans have agreed to co-sponsor Lawler’s bill. “I sent a memo out to all of my colleagues asking them to sign on, and I’ve had one-on-one conversations with Democrats who agree things need to change. But whether or not they sign onto the bill is another discussion,” he tells me. When I ask him why he thinks they’re acting cagey, he says that some may be afraid of losing the few resources they already have. “Generally speaking, staff allotment comes through leadership, and I think people are hesitant to push back.”

Still, Lawler predicts that it’s only a matter of time before the dam breaks on this issue. “I think people are recognizing - especially now when we talk about fair pay for healthcare workers, workers who help people with disabilities, pay equity in the private sector - they’re recognizing it’s hypocritical to not ensure equal pay for those who work in government too.” He also emphasized that he doesn’t want his bill to be a mere political tool for hammering Democrats. “Ultimately, I’d be more than happy to work with my colleagues in the majority to come up with a bill that can garner a lot of support and get it across the finish line.”