Professional Losers: The Transformation of the Democratic Electorate

Between 2008 and 2020, the share of working-class voters in the Democratic presidential primary shrank, while the share of affluent voters grew substantially.

Over the past few years, the press has reported with interest on the fact that the Democratic Party’s popularity seems to be dwindling among the working class, but booming with affluent professionals. Most coverage has focused on how the voting patterns of these groups are changing in the context of general elections. Some coverage has also examined how the party’s coalition is shifting in the context of Democratic primaries, but it tends to be narrower in focus and heavier on anecdotes. For greater insight into these trends, let us consider how the class composition of the Democratic presidential primary electorate shifted between 2008 and 2020.

Such an exercise requires a degree of caution. Many states use the unrepresentative caucus format to conduct their primaries, states may change their primary format from one cycle to another, and a candidate may secure the nomination before each state has voted. For these reasons, it can be challenging to detect changes in the nature of the electorate over time. To avoid these problems, let’s take a look at primary results only in states that used the election format in both 2008 and 2020 during a competitive phase of the nomination process.

There are 16 such states, and in both years, they accounted for about half of all votes cast in the Democratic presidential primary. In almost all of them, the trend is the same: poor and working-class voters are shrinking as a share of the electorate, while the share of middle-class and affluent voters is growing. As we dive into the details, recall that the median household income (MHI) in the US is about $68,000/year.1

Counties where the MHI is under $60,000/year went from contributing 35.3 percent of the presidential primary vote in this cohort of states in 2008 to just 28.6 percent in 2020. By contrast, the share of the primary electorate residing in counties where the MHI is over $80,000/year rose from 24.5 percent in 2008 to 30.7 percent in 2020, with about half of that growth in counties where the MHI is over $100,000/year. But this trend was not uniform across every state. In some, the Democratic coalition barely shifted at all. In others, the transformation was breathtaking.

In Virginia, counties where the MHI is under $60,000/year accounted for 32 percent of the vote in 2008, while counties where the MHI is over $100,000/year accounted for 34.4 percent. But in 2020, the state’s poorest counties contributed just 25.3 percent of the presidential primary vote, while the richest counties contributed 41.4 percent. In North Carolina, the share of the electorate from counties where the MHI is under $60,000/year plunged from 62.2 percent in 2008 to 51 percent in 2020. In South Carolina, the electorate shifted away from poor and working-class counties and toward middle-class counties by 20 points during the same period. In Florida, the shift was nine points.

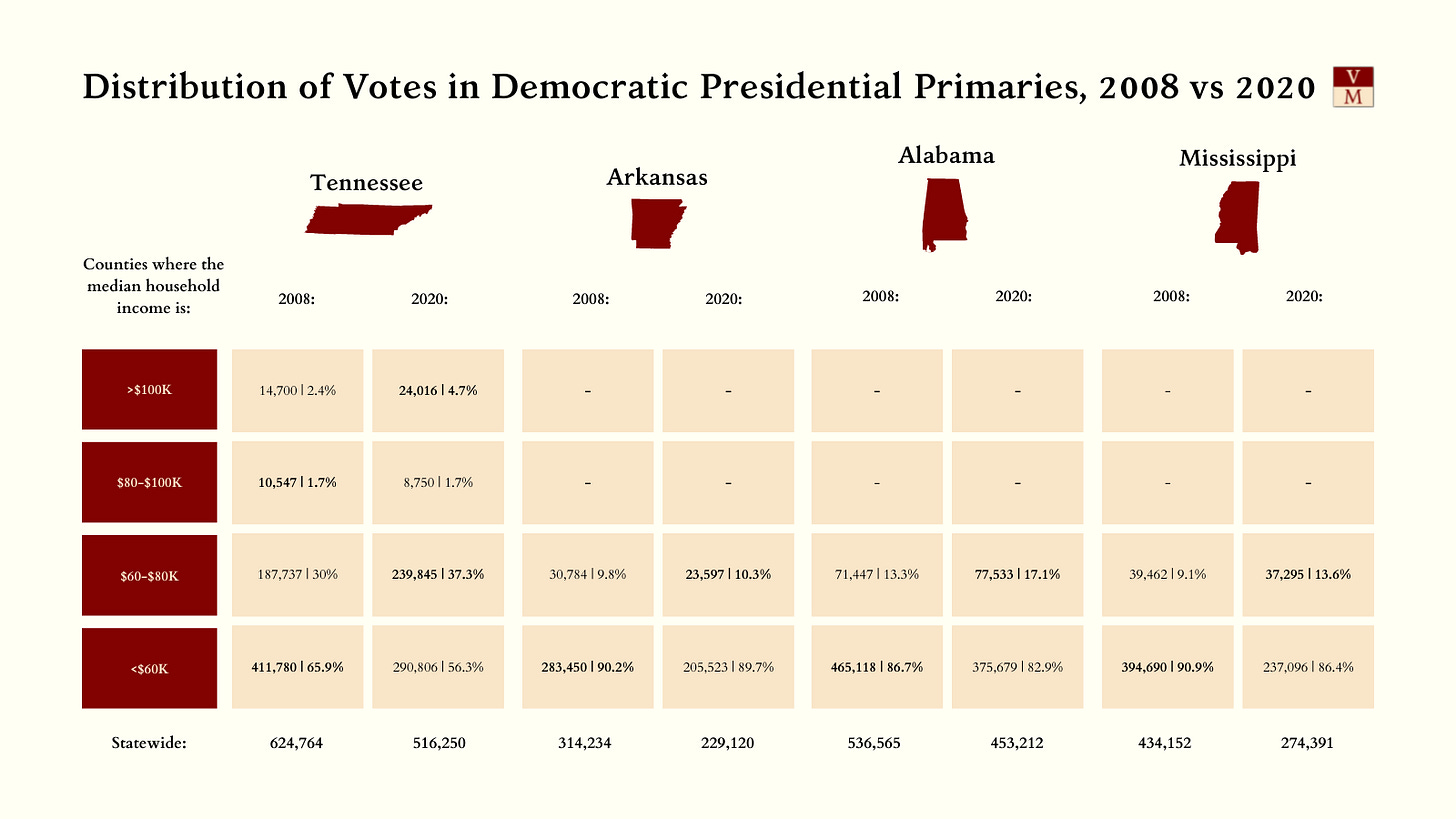

These changes have occurred not only because the party is growing in prosperous areas, but also because it’s collapsing in struggling ones. For example, middle-class counties in Tennessee grew as a share of the electorate from 30 percent in 2008 to 37.3 percent in 2020, and their raw vote shot up by more than 50,000. But poorer counties went from representing 65.9 percent of the electorate in 2008 to 56.3 percent in 2020, and their raw vote plunged by over 120,000. In Alabama and Mississippi, turnout in middle-class counties barely budged between 2008 and 2020, but it tanked in the poorest areas of both states. In Arkansas, turnout fell across all income categories, though the distribution of votes among them remained the same.

The reshuffling of the Democratic coalition has been most dramatic in the South, where partisan polarization along the axes of class, race and education long ran in the opposite direction of recent trends. In the Northeast, where polarization along these lines has historically been less intense, shifts in the electorate have been much smaller. No real change is evident in New Hampshire between 2008 and 2020. In Massachusetts, the share of the electorate from counties where the MHI is over $100,000/year has grown slowly but steadily, eclipsing 40 percent in 2020.

The pace of change in the Midwest - as you might expect - falls somewhere in the middle. Between 2008 and 2020, the presidential primary electorate in Missouri shifted almost 10 points away from counties where the MHI is under $60,000/year and toward counties where it’s higher. In Illinois, no significant change is evident during this time period. Due to Michigan’s botched primary in 2008, it’s not prudent to compare that election to the one in 2020. Prior to that, Michigan Democrats used the caucus format, so comparing 2020 to earlier years isn’t reasonable either.

But Michigan did have a competitive primary in 2016, so while I’ve excluded it from the aggregate data, I’ll describe the shift in its electorate here anyway to highlight how these trends can be meaningful even over short time periods. Between 2016 and 2020, the Democratic coalition in Michigan shifted six points away from counties where the MHI is under $60,000/year and toward counties where it’s higher, with the bulk of that movement in counties where the MHI is over $80,000/year.

In the Southwest, the record is mixed. Arizona and Oklahoma saw a moderate shift in the electorate away from poorer areas toward wealthier ones between 2008 and 2020, while the shift in Texas was more substantial. Counties where the MHI is under $60,000/year went from contributing around 40 percent of the Texas primary vote in 2008 to around 30 percent in 2020. Counties where the MHI is $80-100,000/year contributed just 15 percent of votes in 2008, but nearly 25 percent in 2020. In California, no significant change is evident during this time period.

What accounts for such profound changes to the Democratic coalition? Some argue that the cultural aesthetic of liberal professionals has become toxic among voters without a college degree, and that the working class doesn’t share progressive activists’ enthusiasm for policy disruption either. Others believe that the party has squandered its credibility with working-class voters by failing to pursue a robust economic agenda. The former perspective counsels Democrats to move to the center on culture, the latter urges them to move left on economics. Readers will know that the company line here at Vulgar Marxism is that ideally, Democrats should do both. But the truth is that these trends are decades in the making, and it’s unclear at best if any strategy has the potential to arrest or reverse them.

Beginning in the mid-1960s, the Democratic Party’s traditional base in the white working class started defecting to Republicans, kicking off the slow-motion collapse of the New Deal coalition. Over the next decade, top Democrats began contemplating how to attract new constituencies that could replace the voters that they were hemorrhaging to the GOP. In December 1976, Jimmy Carter’s pollster Pat Cadell wrote a memo arguing that the party’s best bet was to capture the ballooning cohort of college-educated professionals emerging from the country’s transition to a post-industrial economy:

“Caddell argued that if Democrats wanted to create a new ‘political alignment,’ they had to reach ‘the younger white-collar, college-educated, middle-income suburban group that is rapidly becoming the majority of America’...These ‘white-collar and professional’ voters, Caddell warned, ‘were cautious on questions of increased taxes, spending, and particularly inflation.’

Caddell also urged Carter to pay attention to twenty-five-to-thiry-five-year-old baby-boom voters…“Younger voters,” Cadell wrote, “are more likely to be social liberals and economic conservatives.”

Caddell had grasped, if imperfectly, what the electorate of the future would look like, particularly the impending dominance of the suburbs, the rise in education levels, the shift away from blue-collar work, and the importance of professionals.”

Caddell called for the development of an agenda that catered to this cohort’s liberal cultural sensibilities and moderate economic views, one that eventually came to be known as neoliberalism. This ideology emerged victorious from the internecine battles that roiled the party in the 1980s, culminating with the election of Bill Clinton in 1992. Though the Clinton years saw new milestones in the country’s partisan realignment, Democrats still enjoyed enough support from the white working class that it remained an important constituency, if no longer a dominant one. As a result, the Clinton administration was often riven by contradictions - particularly in the realm of social policy - as it sought to satisfy different members of its coalition at different times.

Though they were willing to ban same-sex marriage and execute the handicapped from time to time in order to mollify conservative white workers, the party’s neoliberal wing resisted any concessions to them on economic grounds. And what it wanted more than anything was the chance to move further in the direction of social liberalism and economic conservatism. When Al Gore lost the presidency to Geoge W. Bush in 2000, people like Al From - the founder of the Democratic Leadership Council - and Clinton pollster Mark Penn aruged that Gore’s support for gun control or gay adoption hadn’t alienated the white working class. Rather, his populist economic rhetoric had alienated the white professional class:

“The DLC and Penn blamed Gore’s loss on his adoption of a populist appeal in the last months of the campaign…‘Gore chose a populist rather than a New Democrat message,’ From wrote…‘By emphasizing class warfare, he seemed to be talking to Industrial Age America, not Information Age America.’

Penn wrote that Gore ‘missed the new target of the 21st century: the wired workers.’ He failed to reach ‘middle-class, white suburban males, many of whom had voted for Clinton in the past.’ Gore’s ‘old-style message sent him tumbling in key border states…they were turned off by populism.’”

These quotations are from the fourth chapter of “The Emerging Democratic Majority,” by John Judis and Ruy Teixeira. Published in 2002, this book is mostly remembered for its prediction that changes in racial demography would lead to Democratic dominance over American politics, just as soon as the non-white share of the electorate was big enough. Why the book is remembered this way when its argument is almost the exact opposite is something of a mystery.

Like many of their contemporaries, Judis and Teixeira agreed that college-educated professionals should be the party’s new base. But they also emphasized that a base does not a majority make, and that Democrats must supplement their support from the professional class with support from various other constituencies. Certainly, most of them would be communities of color. But for the emerging Democratic majority to be national and durable, it had to include a decent chunk of the white working class too. “The key for Democrats,” they wrote, “will be…in discovering a strategy that retains support among the white working class, but also builds support among college-educated professionals and others in America’s burgeoning ideopolises.”

To strike this balance, Judis and Teixeira recommended a policy agenda that they called “progressive centrism.” Instead of pacifying the white working class with Sistah Soulja moments while shipping their jobs to Mexico, they advised Democrats to just take their foot off the gas on neoliberalism. As long as they avoided spooking liberal professionals on economics and alienating non-college whites on culture, the party could safely pursue a more conventional center-left agenda:

“Today's Americans…want government to play an active and responsible role in American life, guaranteeing a reasonable level of economic security to Americans rather than leaving them at the mercy of the market and the business cycle. They want to preserve and strengthen social security and medicare, rather than privatize them. They want to modernize and upgrade public education, not abandon it. They want to exploit new biotechnologies and computer technologies to improve the quality of life. They do not want science held hostage to a religious or ideological agenda. And they want the social gains of the sixties consolidated, not rolled back; the wounds of race healed, not inflamed.”

In 2008, Barack Obama captured the presidency with exactly the coalition that Judis and Teixeira described: young people, racial minorities, college-educated whites in the Sun Belt, and non-college whites in the Rust Belt. In 2012, he successfully reassembled that coalition, becoming the first Democratic president to win consecutive popular vote majorities since Lyndon Johnson. He governed along the same lines that they recommended, about halfway between Bill Clinton and Elizabeth Warren. And despite the party’s wipeouts in Congress and at the state and local level during the Obama administration, by November 7th, 2016, almost everyone in politics believed that an enduring Democratic majority had finally emerged. The next day, it was gone.

When I interviewed Teixeira back in February, he told me that the reason for the collapse of the emerging Democratic majority in 2016 was twofold. First, liberal professionals grew contemptuous of anyone who didn’t share their cultural politics, alienating the white working class segment of the Obama coalition. Second, their dismissal of these voters’ economic pain as an excuse for racism allowed Donald Trump to push his advantage with non-college whites to blockbuster margins. To make matters worse, liberal professionals have only grown more insular and censorious over the past six years. Evidence is emerging that non-college non-whites - Asian and Hispanic voters in particular - are drifting rightward as well, as the Democratic brand has become increasingly associated with the woke aesthetic.

No argument here, I told him. But what else did he expect from the professional class? They always prefer to push the envelope on culture to prove their progressive bona fides rather than pay a nickel more in taxes. It’s no coincidence that the most explosive theater of the critical race theory war has been Loudoun County, Virginia (median household income: $152,000). These are the voters that the Democratic establishment has been chasing for 50 years. Now the chickens are coming home to roost, and they’ve got Ibram X. Kendi tucked under their little white wings. If the party wanted its base to be the multiracial working class, shouldn’t it have made them a better offer than “progressive centrism?”

If only it were that simple, Teixeira answered. He told me that not only do many working-class voters not support a left-wing economic agenda, but for those who do, economics is not always the issue that most informs their vote. A candidate who can’t satisfy their demands on higher salience issues won’t even get a hearing on economics.

I have to admit, he’s got me there. In 2020, a socialist candidate had a better shot at the Democratic presidential nomination than at any other time in the party’s history in the person of Bernie Sanders. Post mortems on the Sanders campaign have reached all sorts of conclusions about what went wrong, and some have even cited the party’s professional-class takeover as a big reason for his defeat. But I’m afraid that just isn’t the case. In the 21 states that held Democratic presidential primary elections (excluding caucuses) before the declaration of national emergency concerning the coronavirus pandemic on March 13th, 2020, Biden beat Sanders across all income categories, and Biden’s margin was greatest among the poorest voters.

But as with the changes to the electorate’s class composition, this outcome was not uniform across every state. Sanders lost by devastating margins in poor and working-class counties in the South - where the vast majority of Democratic voters are black - making no improvement on his 2016 performance in these areas. He also failed to make gains with black voters in the Midwest, but suffered major defections among the poor and working-class Midwestern whites who backed him in 2016. Sanders had better luck with downscale whites in the Northeast, where he fought Biden to a draw, but still came in under the margins he notched in his last campaign.

But it wasn’t all doom and gloom for the political revolution. Things were sunnier west of the Rocky Mountains, where Sanders beat Biden across all income categories in multiple states. In fact, he often notched his best performances in poor and working-class counties, including in California, which accounted for a quarter of all votes cast nationwide prior to March 13th. Sanders’ popularity among Hispanic voters was critical to his success in this area of the country. Chuck Rocha, the architect of the campaign’s Hispanic outreach program, credits its success to the decision to eschew social justice rhetoric and appeals to identity in favor of bread-and-butter economic themes that resonate with immigrant families.

One more little ray of sunshine for the left is that the economic profile of Sanders’ coalition in this cohort of 21 states closely tracked the economic profile of the overall electorate in them. In other words, his support wasn’t disproportionately concentrated in any one income category - unlike the other purported occupant of the primary’s “left lane.” In 2020, Sanders really did build a movement of the multiracial working class, even if Joe Biden built a bigger one. Perhaps in the future, another socialist candidate will succeed in this endeavor. But the window to do so closes a little more each year. Sanders’ coalition mirrored the Democratic electorate of 2020, not 2008. If the left continues to market itself to the baseline voter in Democratic primaries, it runs the risk that its own coalition will start drifting up the economic ladder too.

County-level results for the 2008 and 2020 Democratic presidential primaries were sourced from the Atlas of US Presidential Elections. County-level income data was sourced from the Economic Research Service of the USDA. To view the combined dataset, click here.

Quick question: is your income threshold in real or nominal terms? I wasn't sure. Thanks responding and I have enjoyed this newsletter