Someone Needs to Investigate New York’s Commission on Judicial Nomination

The commission is backdating documents to conceal previous members, and Kathy Hochul hasn't released Madeline Singas' financial statements, as required by law.

The Court of Appeals is the highest court in New York State, consisting of one chief judge and six associate judges. In addition to hearing cases, the chief judge also performs an important administrative function as the chief executive of the entire New York Unified Court System. Given the sheer number of people subject to its jurisdiction, and the degree to which our laws structure market conditions for broad swaths of the American economy, the Court of Appeals is a state institution with a national profile. For all these reasons, its integrity is of the utmost importance.

It’s also why an appropriate authority should start looking into the body responsible for selecting its nominees, the Commission on Judicial Nomination. Public records suggest some unusual goings-on that are worthy of closer scrutiny.

Typically, the commission has twelve members. The governor and the chief judge both choose four, and the top Democrat and Republican in both chambers of the state legislature choose one a piece. Whenever a vacancy occurs on the Court of Appeals, the commissioners solicit applications for the open seat, evaluate the candidates, and forward a list of finalists to the governor. By law, the governor must select a nominee only from among those remaining candidates. That’s how former Nassau County district attorney Madeline Singas was nominated to the court by former governor Andrew Cuomo earlier this year, then confirmed by the State Senate in June.

As I reported last week, Singas routinely omitted required information from her financial disclosure forms when she was Nassau DA, a fact which never came to light during her rushed confirmation process. This included rental income from at least two and possibly three different properties in Queens County, as well as the business relationship between her husband’s employer and dozens of Nassau County agencies, including her own office. If these omissions were deliberate, she’d be guilty of a misdemeanor. That’s a factual question that only a formal inquiry could answer, and there are quite a few entities that could perform one - including the Nassau DA’s office. But don’t take my word for it, take it from Madeline Singas.

In 2015, Singas issued subpoenas for the financial records of a number of Republican political clubs on Long Island she suspected of failing to file their own required disclosures. In 2016, she began investigating former North Hempstead Democratic Party chairman Gerard Terry, whom she eventually convicted of tax fraud. Among the many aspects of Terry’s dealings that she examined were “any financial disclosure statements filed with the Town of North Hempstead Board of Ethics in Terry’s capacity as a party officer.”

By her own actions, Singas has acknowledged that suspected lapses in financial disclosure are legitimate grounds for law enforcement investigation. In her case, the lapses aren’t even suspected - they’re discernible plain as day from public records. It is inappropriate in the extreme that she be allowed to sit in judgement over the appeals of criminal defendants while she herself may be guilty of criminal acts - and not only from her time as district attorney.

Applicants for open judgeships on the Court of Appeals must furnish the Commission on Judicial Nomination with a sworn financial statement documenting their “assets, liabilities and sources of income, and any other relevant financial information which the commission may require.” According to Article 3A of the Judiciary Law, once the governor has selected a nominee: “The governor shall make available to the public the financial statement filed by the person who is appointed to fill a vacancy.” After Singas was confirmed to the court in June, Cuomo simply ignored the law, as was his custom.

Our new governor, Kathy Hochul, has promised a break from the guarded secrecy and open lawlessness of the Cuomo era. If Madeline Singas concealed information on her sworn statement to the Commission on Judicial Nomination - as she did on her county disclosure forms every single year she was Nassau DA - she may be guilty of perjury as well. Hochul should immediately produce this document so that the public can examine it, as required by law.

This is all the more urgent in light of additional facts that suggest Hochul and the commission may be trying to obscure the role of a Cuomo crony in the selection of Singas as a finalist for the court in the first place.

If you look at the directory as it appears right now on the commission’s website, you’ll see only eleven names listed. Who’s missing?

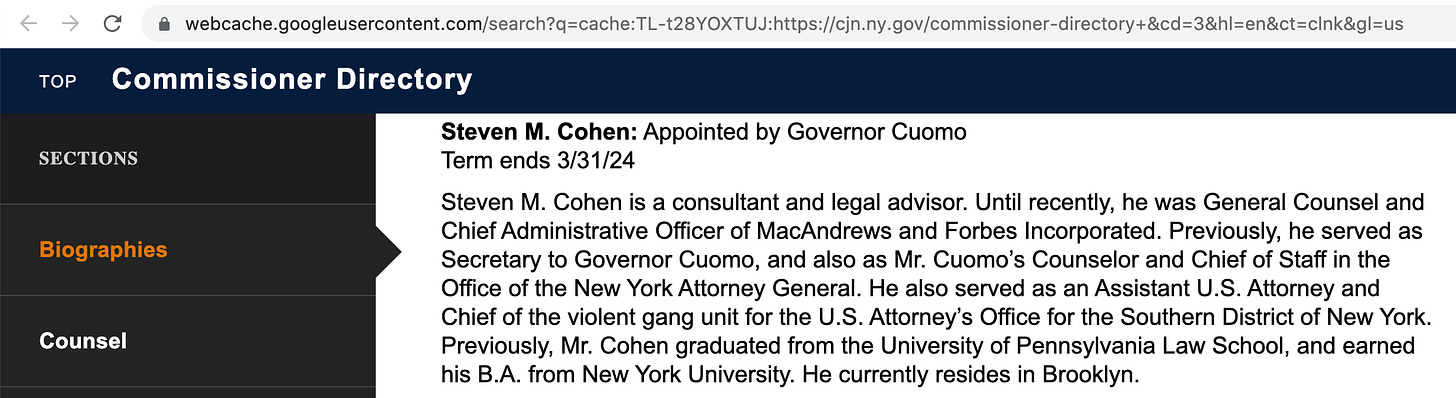

The answer is Steven M. Cohen, a Cuomo advisor and fixer for more than a decade. Cohen was named in New York Attorney General Letitia James’ report on accusations of sexual misconduct against Cuomo as being among those implicated in the scheme to discredit Lindsay Boylan, one of the former governor’s accusers. He later claimed to be working as an attorney for Cuomo at the time.

The day after Kathy Hochul assumed the governorship, her office announced that Cohen was resigning as chairman of the state’s economic development corporation. Spectrum News reported that “Hochul has said anyone who was implicated in the attorney general's report would not have a place in her administration,” but it’s not clear if this is their own analysis or the reason her office gave for Cohen’s departure. No other outlet appears to have reported on his removal.

Also unclear is why Hochul’s office would announce that Cohen had left this position, but not mention that he resigned from the Commission on Judicial Nomination as well. Both appear to have happened around the same time. A cached version of the commission’s website shows that as recently as August 17th, Cohen was still listed in its directory, with his term scheduled to expire in 2024.

Updating the commissioner directory to reflect current membership is one thing. But there was another, more troubling change to the website made sometime in the past two weeks. One of the main tabs at the top of the homepage is entitled “Brochure,” and links to a PDF document containing a two-page description of the commission, its duties, and its members. But notice that despite being dated January 2021, when Cohen was still on the commission, his name is nowhere to be found.

A cached version of the old document still survives on Google, allowing us to see that Cohen’s name did indeed appear on the document’s previous form. The metadata of the new one shows that it was created on August 26th, 2021, the day after Hochul’s office announced Cohen’s resignation from Empire State Development.

Now, perhaps the commission would say it merely wanted to be comprehensive in updating the website to reflect its current membership, and so it revised the brochure as well as the directory. But the brochure’s list of commissioners is clearly labeled “January 2021.” The decision to preserve that label gives the impression that it either wanted readers to believe that there had been no changes in the body’s membership that year, or didn’t care if they made that false assumption.

Moreover, the commission’s failure to actively publicize a vacancy under Hochul is a continuation of its Cuomo-era practice of violating its own rules. The Judiciary Law empowers the commission to set the internal procedures by which it carries out its mandate. According to those procedures, when a vacancy occurs on the commission, “notice will be published on the commission's website, distributed to the media, bar associations throughout the State and other persons and organizations.”

But if the commission’s website is to be believed, the last time this occurred was in January 2012, when it issued a press release announcing that the terms of three members were about to expire. Though the first line of that document acknowledges that the announcement is “pursuant to its rules,” no similar press releases giving notice of vacancies appear on its website after that date.

Nevertheless, it’s still possible to use the press releases it did issue to reconstruct its membership history. Every time it puts out a statement, the commission lists all of its current members in the top lefthand corner. If you go through them chronologically, you can get a rough idea of who served on it and when. By this method, we can see that other changes to the brochure were made earlier in the year, including yet another Cuomo crony whose name was scrubbed even more thoroughly than Cohen’s was.

In December 2020, only nine people were serving on the Commission on Judicial Nomination. Why a full quarter of the seats on this important body were empty at the time is unknown, as it doesn’t observe its own protocols for informing the public about vacancies. But by March 2021, all three had been filled, and another commissioner was appointed to replace one whose term expired. Among the new names on the commission’s March press release was Simone M. Levinson, who served a previous term on the body that ended in 2017. Who is Simone Levinson? Allow me to draw your attention to this profile of her in Hamptons Magazine from 2013:

Simone is a former actress and ballet dancer, and current wife of the wealthy real estate developer David Levinson. These days, she mostly seems to occupy her time patronizing the arts in the Hamptons, renovating $50 million townhouses on the Upper East Side, and attending lavish parties with Chris Cuomo. And before you object that surely this is a different Simone Levinson, note that this profile mentions her service not only on the Commission on Judicial Nomination, but on New York’s Spending and Government Efficiency Committee as well. She’s certainly qualified - these gigs only cost her and her husband $88,000 to Cuomo’s reelection campaigns.

Levinson’s name appeared on two press releases this year, one from March and one from April. After that, she’s replaced by Abraham Lackman, a longtime Republican operative and another Cuomo ally. Curiously, only the March release with Levinson’s name is available on the commission’s website; the one from April is missing (the link to it above is from the New York State Bar Association). It also happens to be the one announcing Madeline Singas as a finalist for nomination to the Court of Appeals.

You don’t even need to entertain the idea that the commission chose Singas for her perceived loyalty to Cuomo in order to acknowledge how poorly it’s being run. Wealthy campaign donors with no relevant expertise should not be able to purchase a seat on a body charged with such sensitive work. And it’s frankly outrageous that a commissioner would be allowed to act as a personal attorney to the governor while having influence over nominees who may have to vote on whether or not to remove that governor from office.

The commission’s lack of transparency with regard to its membership and routine violation of its own rules only exacerbates the appearance of impropriety. And it makes Hochul’s attempts to quietly remove Cohen by exploiting these deficiencies, as opposed to fixing them, all the more inappropriate. She needs to whip this commission into shape, and if she refuses, the legislature should exercise stricter oversight.

Neither do you need to entertain the idea that the commission chose Singas for her perceived loyalty to Cuomo in order to acknowledge that Hochul is legally bound to release Singas’ financial statement. And not just any financial statement, such as any she may have filed with the court system. The judiciary law is clear: the governor must release the sworn financial statement provided to the Commission on Judicial Nomination for purposes of evaluating her candidacy for the Court of Appeals.

Still, you can’t help but wonder whether a secretive commission stacked with Cuomo cronies - including his personal attorney - did have Singas’ perceived loyalty to him in mind when selecting the finalists. She certainly seems to be a fan of his work.