Will Twenty Years of Republican Gains Among the Working Class Continue?

Over the past six presidential elections, the GOP made substantial inroads in poor and working-class areas of the country. They’re on track to make even more.

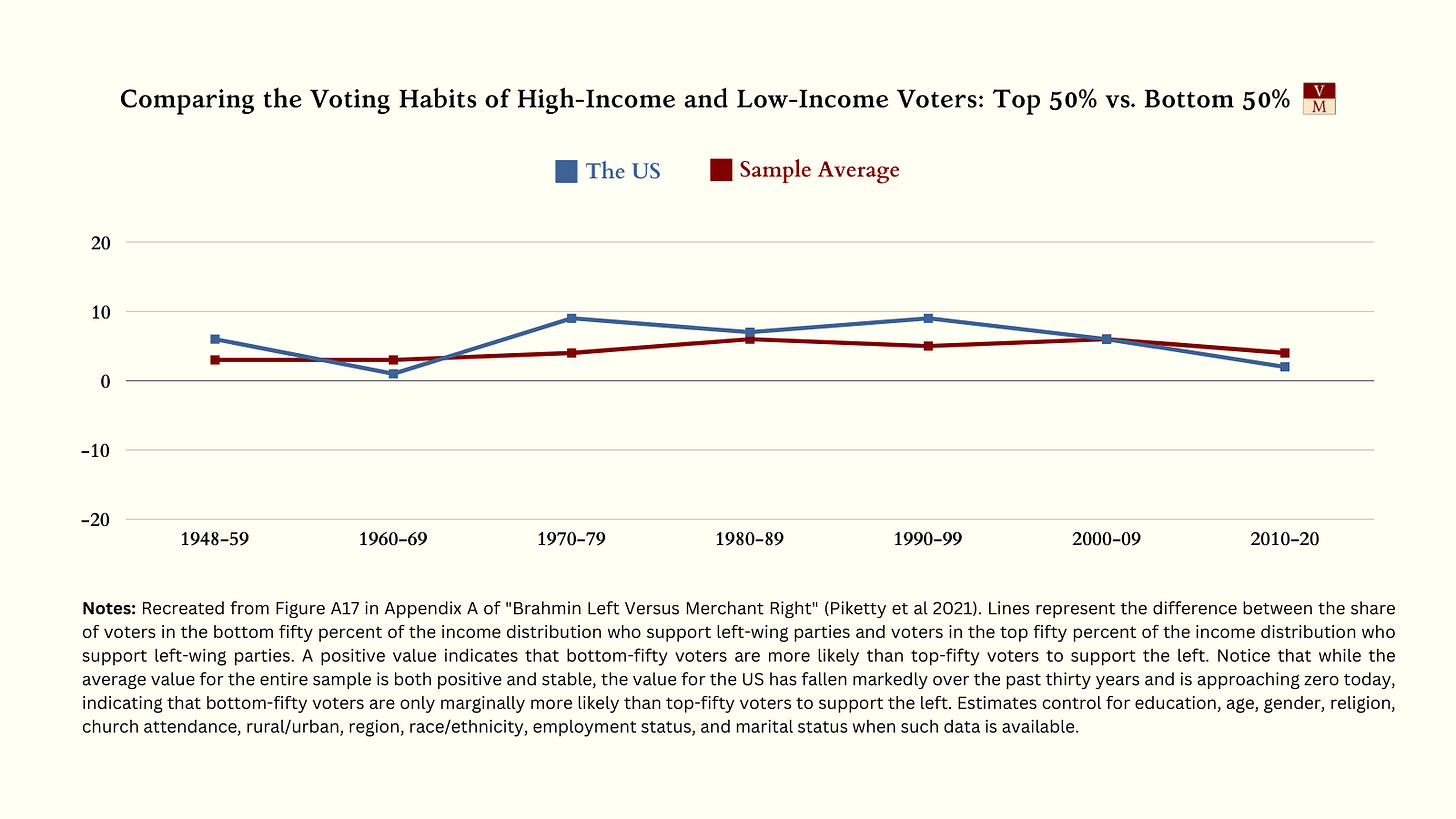

Many people are saying that low-income voters are moving to the right while high-income voters are moving to the left – but is that really true? Well, it all depends on which voters you’re talking about. A 2021 study by Amory Gethin, Clara Martínez-Toledano, and Thomas Piketty analyzed survey data from twenty-one Western democracies and calculated how respondents from various income groups voted in each of their countries’ national elections between the mid-20th century and 2020. They found that:

“In the 1960s, the effects of income and education on the vote were aligned: higher income and higher education were both associated with higher support for conservative and affiliated parties. By 2016–2020, these two variables now have opposite effects: higher income is associated with higher support for conservative parties, whereas higher education is associated with greater support for social democratic parties.”

Furthermore, Piketty and coauthors found that while rich voters have continued supporting the right, poor voters have continued supporting the left. “We do not see a dissipation of income-based left-wing voting in Western democracies,” they explained in a 2022 interview with Jacobin. “Low-income voters continue to support left-wing parties just as much as in the past.” Certain writers and activists have pointed to this study as evidence that all the hand-wringing over so-called “class dealignment” – which has dominated American political discourse since the rise of Donald Trump – is misguided.

Unfortunately, such writers and activists failed to read the fine print. What Piketty and coauthors described in that Jacobin interview was the average trend across their entire sample of countries. But there are large variations in their findings between countries, and here in the US, things are moving in the opposite direction. Several graphs in their appendix demonstrate this fact, but quite frankly, they’re pretty cluttered and hard to read. I’ve taken the liberty of recreating a few of them to improve their legibility with respect to the US.

Over the past forty years, Democrats dramatically improved their performance among voters in the top ten percent of the income distribution, with the trend accelerating over the past twenty. Meanwhile, the party peaked among voters in the bottom half of the distribution in the 1990s and has been on a steady downward trajectory with them ever since. Such patterns set the US apart from almost all other countries in the study, which haven’t seen nearly the same level of change to the class character of their left-wing and right-wing coalitions. This is why the Piketty group says in their paper that “the only country where a flattening of the income effect [read: class dealignment] could well be underway is the United States.”

Earlier this year, John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times cut the dataset that Piketty and coauthors used somewhat differently and observed a similar pattern. His analysis found a strong improvement in Democratic performance among voters in the top third of the income distribution and a concomitant improvement in Republican performance among voters in the bottom third. Thus, no matter how you slice the numbers, they do seem to suggest that class dealignment is a real phenomenon - at least here in the US. But just how reliable are these numbers anyway?

The dataset in question comes to us from the American National Elections Studies (ANES) project at the University of Michigan. Every presidential election year, ANES recruits a large sample of voters designed to represent the national electorate, then surveys those voters before and after the election. If ANES succeeded in recruiting a representative sample, then the results of the survey asking respondents whom they voted for should mirror the actual election results. Unfortunately, ANES struggled to do this in 2020, compromising the value of its data for that year and casting doubt on any conclusions drawn from its analysis.

To see the problem, let’s compare the results of the ANES survey with the FiveThirtyEight polling average for each of the past six presidential elections. Prior to 2020, the largest polling error for both outfits occurred in 2000, when the FiveThirtyEight model produced a four-point Republican margin of victory in the national popular vote while the ANES survey produced a five-point Democratic margin. In fact, Al Gore won the national popular vote by a single point that year, giving a polling error of five points for FiveThirtyEight and four points for ANES - though in opposite directions. Over the next four cycles, both outfits correctly modeled the eventual winner, and neither had a polling error of more than four points. In each cycle, ANES had a slight Democratic bias, while FiveThirtyEight had a slight Republican bias in 2012 and a slight Democratic bias in 2016. No model or survey is ever perfect of course, and all things considered, both outfits modeled these elections reasonably well.

But things changed in 2020 – for one of the outfits, anyway. Prior to the election, FiveThirtyEight predicted an eight-point Biden victory, and since Biden won the national popular vote by only four points, that gave them a four-point polling error with a slight Democratic bias. Such a result is in line with their previous errors and not too severe of a miss. However, the ANES sample of voters in 2020 favored Biden by a whopping eleven points, giving them a seven-point polling error with a considerable Democratic bias.

The fact that ANES performed so much worse than the public polls in 2020 came as something of a shock. For decades, scholars have regarded the project as the gold standard in American public opinion research, and its data forms the basis for much of the high-quality, quantitative scholarship in the social sciences. Only a small handful of organizations have been measuring public opinion on the same cluster of topics at regular intervals for more than a few decades, and of these, ANES is the oldest and deploys the most detailed surveys. Thus, it’s the single best resource that scholars have for tracking changes in public opinion over time. If the quality of its data starts to decline, it could become difficult to assess the trajectory of trends that were observed in elections past. For this reason, ANES has a strong interest in identifying what went wrong in 2020 and ensuring that such problems don’t crop up again.

At the annual conference of the American Association for Public Opinion Research in May 2023, two of ANES’ principal investigators presented a paper on exactly this question. This time around, they sent follow-up surveys to all the people who failed to respond to their initial recruitment drive when they were building their 2020 sample of voters. The results suggest that nonrespondents are less likely than respondents to have a college degree and internet access at home. Nonrespondents are also more likely to have concerns about privacy and exhibit less social trust than respondents. Nonrespondents are also more likely to have voted for Trump, and further analysis suggested that Biden-voting Republicans were overrepresented in ANES’ 2020 sample. The investigators hope to use these insights to improve the quality of their voter sample in 2024.

Of course, there are limits to what we can know about nonrespondents and how much more we can do to induce their cooperation. The conclusions above are based on surveys of people who failed to respond to ANES’ initial recruitment drive, but did choose to respond to follow-up surveys asking why they failed to respond in the first place. It could be the case that the people who failed to respond to both surveys are substantially different from the people who only responded to the follow-up survey, and there’s no way to know because such people simply refuse to engage with researchers at all - a possibility that the investigators acknowledge in their paper.

The only thing we can say for sure is that for whatever reason, ANES significantly under-sampled Trump voters in 2020. Thus, while it may be reasonable to suspect that the general trend of class dealignment continued in that election, the exact levels of support that the two parties drew from various income groups must be regarded with a higher degree of skepticism than the levels measured in elections past. It’s also difficult to say whether the trend toward class dealignment would have appeared stronger or weaker if ANES had achieved a more representative sample; it all depends on the class position of this inscrutable group of survey-skeptical Trump voters.

With any luck, ANES’ 2024 survey will more faithfully reproduce this year’s election results. But there is another, more disquieting possibility: that the social forces discouraging Trump voters from engaging with the project have only intensified over the past four years, and that future surveys will exhibit an even stronger Democratic bias. If that does turn out to be the case, scholars will have to rely on alternative methods for assessing the trajectory of class dealignment. Let’s consider one of them now.

For this piece, I collated the results of the last six presidential elections in every US county and county-equivalent. Next, I identified the median household income (MHI) for each of these localities at the time of each election, then adjusted for inflation to normalize the MHI in 2020 dollars. Finally, I divided the counties into income bands to track how their voting habits have changed over time. Band 1 represents counties where the MHI is above $100,000, Band 2 represents counties where the MHI is between $75,000 and $100,000, Band 3 represents counties where the MHI is between $50,000 and $75,000, and Band 4 represents counties where the MHI is below $50,000. The results are as follows.1

Over the past six elections, Democrats substantially improved their performance in Bands 1 and 2. As a result, Republican performance in both of these bands declined substantially over the same period. Relative to 2000, Democratic performance is stable in Band 3, but the party has seen a modest decline in these counties relative to 2008 and 2012, when Barack Obama managed to win a majority of their vote - the only Democrat to do so in the 21st century. By the same token, Republican performance in Band 3 is stable relative to 2000 and up modestly relative to 2008 and 2012. Finally, Democratic performance has declined substantially in Band 4, while Republican performance has substantially improved.

Of course, not all of these changes are equally as significant when it comes to shaping the outcome of elections. For example, even though Democrats have improved their performance in Band 1 to a greater degree than they have in Band 2, Band 2 accounts for a greater share of the electorate; thus, the party’s improvement in Band 2 has done the most for its bottom line. By the same token, even though Republicans have substantially improved in Band 4, these counties represent only a small share of the electorate - and a shrinking one to boot. In fact, GOP gains among poor voters have been totally overwhelmed by their losses among rich voters and voters in the upper-middle class. These trends are why it’s been twenty years since the party won a majority of the popular vote.

Unfortunately for Democrats, it isn’t the popular vote that determines who sits in the White House. Counties in Bands 3 and 4 are disproportionately concentrated in the Electoral College tipping point states of the Upper Midwest, which is why the past three elections have teetered on a knife’s edge as the returns from these states rolled in.

At any rate, whether the left wants to admit it or not, class dealignment is indeed underway. So far, the process has been most pronounced at the edges of the income distribution – Bands 1, 2, and 4. The real question going into next week is whether the counties in Band 3 – the great mass of the middle class, representing over half of the electorate – will continue their post-Obama lurch to the right. Given their size, a shift of even a few points in these counties could not only hand Donald Trump an Electoral College victory, it could give the GOP its first popular vote majority in twenty years. Maybe then the left would be forced to confront the grim reality that it faces.

County-level results for the elections in question were sourced from the Atlas of US Presidential Elections. County-level income data was sourced from the Census Bureau. To view the combined dataset, click here.