Can Fetterman Reverse Democrats' Declining Fortunes with Pennsylvania's Working Class?

The Lieutenant Governor performed best in the state's poor and working-class regions, where his party has been bleeding support for over a decade.

Last week, I published an analysis showing that poor and working-class voters have declined as a share of the Democratic presidential primary electorate, while the share of affluent voters has grown substantially. On Tuesday, returns from the Democratic primary for US Senate in Pennsylvania showed a similar pattern.1 In 2010, counties where the median household income (MHI) is below $60,000/year contributed 45 percent of the vote in the Democratic Senate primary. In 2022, they contributed just 35 percent. Meanwhile, counties where the MHI is above $80,000/year went from contributing 13 percent of the vote in 2010 to nearly 20 percent in 2022.

Both years featured competitive races that took place during the first midterm cycle after the election of a Democratic president, making them excellent points of comparison. On the GOP side, comparing the results of this week’s primary to the results from 2010 is not as fruitful, since the earlier contest was uncompetitive. However, the Republican Senate primary in 2004 was hotly contested. Against that benchmark, counties where the MHI is under $60,000/year accounted for a slightly higher share of the GOP electorate in 2022, while counties where the MHI is over $80,000/year accounted for a slightly lower share.

While the Democratic coalition is swinging towards the rich and the Republican coalition is swinging towards the poor, the movement on the GOP side is much weaker. This suggests that rather than switching their party registration, many poor and working-class Democrats have simply stopped voting in primaries altogether, though they may still be voting in general elections. But these changes have not been uniform across Pennsylvania, and dividing the state into subregions offers greater insight into where the party is really struggling.

The Philadelphia metro area now accounts for a much larger share of the Democratic electorate than it did twelve years ago. But that growth has been driven entirely by the city’s upscale suburbs, where polarization along the axis of college education has pushed wealthy professionals out of the GOP. Philadelphia itself now accounts for a slightly smaller share of the Democratic coalition than it did in 2010. At the same time, the share of the electorate from the working-class exurbs around Allegheny County has plunged, while the share from Allegheny County itself has grown only modestly.

Smaller metro areas in the Lehigh Valley and the South Central region are also home to more Democratic primary voters than ever before, while the number residing in rural Pennsyltucky is dwindling rapidly. Another area of the state losing its influence within the party is the Wyoming Valley, where my family settled after coming over from Poland about 100 years ago. Like many Polish immigrants, my great-grandfather, Gilbert Paczkoski, was a mine worker in Luzerne County until he died in a mine collapse at the age of 60 in 1967. Even as the industry disappeared in the latter half of the 20th century, the legacy of the United Mine Workers kept Luzerne blue until 2016, when it gained notoriety as the archetypal Obama-Trump county.

Such dramatic changes to the Democratic coalition in Pennsylvania don’t bode well for the party’s general election chances. In 2016, Amy Walter of the Cook Political Report offered Democrats hope that these trends might shake out in their favor, declaring: “For every blue collar and disaffected voter Trump may pick up in Western Pennsylvania, he could lose two or more women in the Philadelphia suburbs.” With the benefit of hindsight, we now know that the state is simply not wealthy nor suburban enough for these changes to be anything but bad news for the party’s competitiveness.

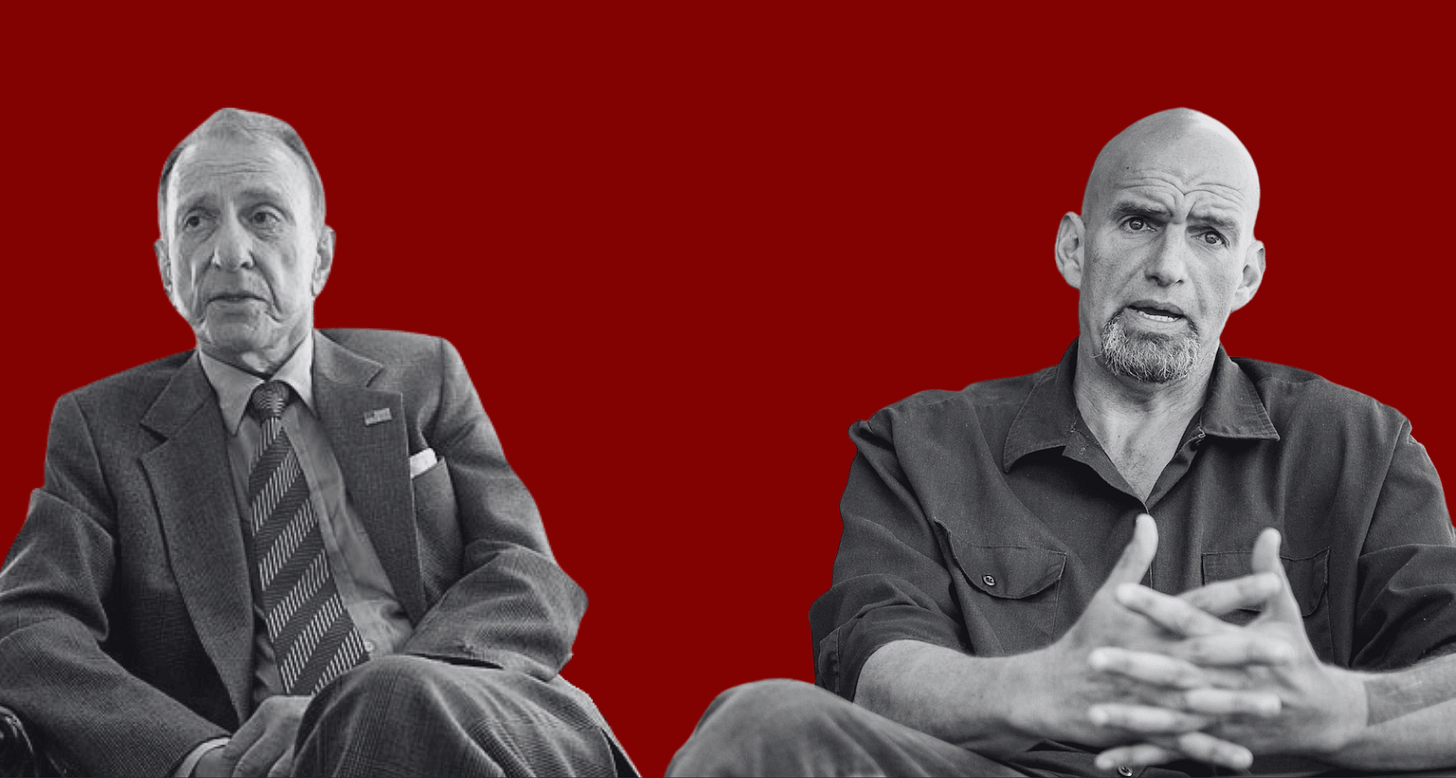

Still, Democrats have selected a formidable nominee who may be able to overcome these challenges. Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman not only won every county in the state on Tuesday, but he posted his best numbers in the regions where Democrats have been bleeding support: the Southwest, Pennsyltucky, and the Wyoming Valley.

Fetterman’s performance is all the more impressive in light of the opposition that he faced from the Democratic establishment, which backed Conor Lamb, and the NGO mafia, which backed Malcolm Kenyatta. The fact that Kenyatta struggled to crack double digits is unsurprising, given the impotence of the progressive nonprofit apparatus on which his campaign was built. But the establishment’s failure to produce a better showing for Lamb is remarkable, especially in Philadelphia. Back in 2010, the city’s Democratic machine was still strong enough to deliver two-thirds of its voters to a bona fide Republican. Well, sort of.

Between 1980 and 2010, Pennsylvania was represented in the US Senate by Arlen Specter. Though technically a Republican, Specter wasn’t exactly a party loyalist. In fact, he was a registered Democrat throughout his early career as a prosecutor in Philadelphia, and he only joined the GOP when the city’s Democratic bosses refused to back him for district attorney in 1965. After he ran and won as the Republican nominee, he finally got around to switching his party registration. Specter served two terms and then chose to remain in the GOP, but he never let partisanship get in the way of politics. When he ran for Senate in 1980, he carried Philadelphia in the general election with the help of dissident factions of the Democratic machine - the last Republican candidate for statewide office to do so.

During his years in the Senate, Specter was open-minded on most social matters. He supported abortion rights and embryonic stem cell research, all the gay rights except for marriage, and he worked to strengthen federal anti-discrimination laws. As a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, he helped sink Robert Bork’s nomination to the US Supreme Court in 1987, though his interrogation of Anita Hill in defense of Clarence Thomas almost cost him his seat in 1992. Specter even ran for president in 1996 as a way of advocating for the GOP to strip opposition to abortion from the party’s platform. All of this infuriated conservative activists, and they spent 25 years trying and failing to defeat him via scorched-earth primary campaigns.

But even more than his social views, what really fueled the right’s hatred for Specter was his greatest quality of all: his serene indifference towards the budget deficit. From his perch on the Senate Appropriations Committee, Specter funneled untold billions into large-scale infrastructure projects throughout the state, provoking the ire of the GOP’s most reactionary elements. Chief among them was the Club for Growth, an organization co-founded by the Pennsylvania billionaire Jeff Yass to promote a far-right economic agenda. In 2004, the group recruited Pat Toomey to challenge Specter in the Republican primary, with the goal of intimidating other moderate senators into tightening up the federal purse strings.

During the campaign, Toomey preferred to emphasize his budgetary critique of Specter when addressing more respectable audiences. But he also knew that it wasn’t his proposal for a flat tax that was going to get people to the polls. Though he’s rebranded himself as something of a social moderate these days, Toomey’s first campaign for Senate was as heavy on the culture war as it was on crackpot economics. From the New York Times, April 3rd, 2004:

“‘If we beat Specter, we won't have any trouble with wayward Republicans anymore,’ said Stephen Moore, president of the Club for Growth, which has spent nearly $1 million on advertisements criticizing Mr. Specter. The club's members have contributed about $800,000 to Mr. Toomey's campaign.

Although the Club for Growth is by far Mr. Toomey's biggest backer, an array of prominent conservatives have endorsed his campaign, including the National Right To Life Committee and the National Taxpayers Union Campaign Fund. Grover G. Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform and James C. Dobson, chairman of Focus on the Family, have also given endorsements.

‘Specter has been a one-man road block to the confirmation of conservative, pro-family judges,’ Dr. Dobson wrote to supporters. He also accused Mr. Specter of helping to block a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage.”

To help suppress this revolt, Specter locked down endorsements from President George W. Bush and Rick Santorum, Pennsylvania’s other Republican senator. The libertarian donors bankrolling Toomey were just as hostile to the compassionate conservatives of the Bush administration as they were to Specter, and the White House was eager to punish their insolence. As a member of Senate Republican leadership, even Santorum honored the party’s policy of backing incumbents for re-election.

Specter also tried to strike a balance between shoring up his conservative credentials and leaning into his reputation as a maverick. His voting record in the Senate took an unmistakable turn to the right, as he sought to deprive his critics of ammunition for further attacks. But he didn’t allow them to set the terms of the debate either. Specter worked to portray Toomey as a fanatic waging a holy war on behalf of wealthy elites. He ran ads declaring that his opponent “isn’t far-right, he’s far out,” and he excoriated the Club for Growth as a gang of “Wall Street tycoons” whose austerity agenda threatened the livelihood of working-class conservatives.

When all the votes were tallied, Specter prevailed in the poorest areas of the state, from Philadelphia to Pennsyltucky, and he crushed Toomey in the hard-up Wyoming Valley. Specter also made a strong showing in the Philadelphia suburbs, who were no doubt turned off by his opponent’s jughooter act. But Toomey had still come within a point of victory thanks to robust support in the middle-class exurbs, the largest segment of the Republican coalition in Pennsylvania.

After losing his first campaign for Senate, Toomey resolved to challenge Specter again at the next opportunity. In the meantime, he took over as president of the Club for Growth, where he busied himself purging the state’s other moderate Republicans from office. In 2006 alone, his group took out 12 incumbents, including two members of GOP leadership in Harrisburg. By the time he announced his second bid in early 2009, Specter knew that he wouldn’t survive a rematch. Not only had the Republican base grown increasingly radical after the election of Barack Obama, but the party institutions whose support he needed were buckling under pressure from the right.

Even though he was pushing 80 years old, Specter resented the idea of being forced into retirement by Toomey’s unholy alliance of voodoo economists and Evangelical snake handlers. So he decided to take a page out of his own playbook. In April 2009, he cut a deal with the Obama White House and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. In exchange for their support for his re-election, Specter would return to the Democratic Party after 45 years. This gambit provided them with the 60th vote they needed to break the Republican filibuster and pass the Affordable Care Act later that year. The refusal of stubborn octogenarians to retire might not be working out for the party these days, but twelve years ago, it saved their agenda.

Unfortunately for Specter, Democratic voters didn’t see it that way. Congressman Joe Sestak decided to challenge him in the Democratic primary of 2010, turning down multiple job offers from the Obama administration for the chance to lose to Pat Toomey in November. Throughout the campaign, Sestak portrayed his opponent as an opportunistic politician clinging to power any way that he could - as if there’s any other kind. But the attacks stuck, and even though the outcome was fairly close, Specter came out ahead in just three of the state’s 67 counties. But poignantly, one of them was Philadelphia. In his final race for Senate, the city had come through for him, just as it had in his first.

But on Tuesday, Philadelphia did not come through for Conor Lamb. Now granted, Lamb hasn’t lived in the city for the past sixty years as Arlen Specter had, nor did he have Barack Obama cutting campaign commercials for him. But he did have the backing of the party establishment. And not only did Lamb come in third citywide anyway, he lost to John Fetterman even in majority-black neighborhoods, where the establishment is most influential. In 2010, Specter crushed Sestak by a three-to-one margin in black neighborhoods, even as they split the white vote down the middle. Maybe next time Lamb should try running as a Republican.

County-level results for the 2022 Democratic Senate primary were sourced from the New York Times. Results for other races were sourced from the Pennsylvania Department of State. Ward-level demographic data for Philadelphia was sourced from Sixty-Six Wards. County-level income data was sourced from the Economic Research Service of the USDA. To view the full dataset, click here.